by Mark “Boxer” Doran

Practice, practice and more practice. That’s an appropriate mantra for learning to be an effective pilot in the Falcon 4 universe. In some ways, the black art of missile evasion is perhaps the epitome of the requirement. Arguably, the evasion of missiles is one of the most challenging aspects of the entire Falcon 4 experience. If you, like me, have been experiencing a little frustration at the hands of the SAMs, take heart…they can be beaten, with a little structured practice.

The purpose of this article is to share some specific advice on how to beat a couple of the SAM types in the Falcon 4 universe. In the process, we will discuss some specific tools and techniques that will help you keep your virtual jet in one piece. Finally, there are some suggestions on how to practice and get better at evading those pesky SAMs. With luck, you may be able to apply the ideas to your own practice and then tell me how best to beat some of the other missile types.

Of course there’s the sound tactical argument: stay out of threat areas and you won’t have to evade missiles. You should, of course, do this as a matter of course. Don’t overfly known SAM sites. Never fly between 500 feet and 10,000 feet over enemy territory. Never fly in straight lines for more than a few seconds. Sound tactics one and all, which work nicely in the mission-planning phase, but often SAM threat location intelligence is imperfect or fighters pop up and wreck your nice safe medium altitude ingress flight plan. Suffice it to say that at some point, even with the best planning to avoid it, you will eventually end up in the heart of a SAM battery’s engagement envelope. When that happens, it is best to be prepared.

By now you have probably read a lot of other material about missile evasion, so you will know about the need to beam radar guided missiles and that showing a “zone five” afterburner-can to a heat seeker is a recipe for a bad day. You may even have read the diatribe about missile evasion in Shaw’s “Fighter Combat” and thus be familiar with the notion of barrel rolling about a missile’s approach axis in the terminal homing phase to shake off said missile. If you are looking for more help in the theory department, Shaw’s book is excellent. And, of course, don’t forget the Falcon 4 manual: there’s a good explanation of missile function in Pete Bonanni’s training mission description starting on page 7-2.

Well, the theory is all very well, but what does beaming look like from the pilot’s-eye view in Falcon 4? And how do you use the view and other situational awareness tools in the game to affect a good beaming maneuver? And what if beaming isn’t enough to shake the threat?

Make the Padlock View Work for You

Assuming a missile within visual range, absolutely the most important thing is to get your “Mark I” eyeball on the incoming weapon. Only then can you evaluate the threat and react effectively to defeat it. The first and most valuable tool in the battle is the padlock view.

If you are using Realistic padlock, you should probably give serious consideration to switching to Enhanced mode. Enhanced padlock is about the only reasonable way you will be able to lock quickly onto a freshly-launched SAM that has your name on it. Most of the people I know flying Falcon 4 who count themselves in the “hard core” crowd normally shun game settings that are less than maximum possible on the realism scale. Even so, it seems that everyone has decided that Enhanced padlock is the only way to go if you are to survive.

That said, there are a couple of tricks to using the Enhanced padlock effectively that can improve your chances dramatically. First, it is important to understand what the manual means when it says the padlock view will lock onto successive targets, highest priority threat first, followed by the next highest and so on with each press of the padlock key (“4” in this case).

What this means in practice is that the game calculates the priority list each time you enter the padlock view and subsequent “4” key presses move on down the threat list.

What it also means is that if you are already in padlock, say lining up a juicy T-62, and a SAM is then launched at you, the next press of the padlock key will NOT switch you to the incoming missile. While in may be tempting to think that each padlock key press should take your eye to the highest threat at that given moment, that isn’t how it works.

If you want to be sure that you latch onto the highest priority target at any given moment, you need to be in some other view and then enter padlock view to be sure if getting the most urgent threat in view. Thus, if you are in fact already in padlock view when you get a launch warning, you must leave padlock view and re-enter it to be sure of latching onto the newly launched threat. At least by observation that seems to be the way it works.

The keypad plus and minus keys don’t help you either, even though you might think they should. Now, pressing minus does in fact take you to higher priority threats. The trouble is that when you reach the number one threat, a subsequent press of the minus key will wrap you around to the other end of the list, a lower priority threat. This, of course, makes the plus and minus keys useless in terms of understanding where the threat you are looking at right now resides in the priority list.

Unless you are prepared for these little details in the game’s implementation, latching onto an incoming missile can be very difficult and frustrating. I can’t take credit for this insight: Falcon 4 Instructor Pilot Stephen “HotdogOne” French taught it to me. He also has a simple but ingenious strategy for programmable HOTAS buttons that bears repeating here, albeit with some extra amplification that Stephen provided for me in a follow-up email to make things clear.

The suggestion is to program a button to issue the sequence to bring up the 2D cockpit and then padlock again immediately. The Thrustmaster F22 button definition I use looks like this:

BTN T1 /O /N Cockpit DLY(30) /N Padlock /I Padlock REM unpadlock-padlock

where the corresponding macro file statements look like this:

Cockpit = 2

Padlock = 4

The small delay ensures that the time needed to switch into 2D cockpit doesn’t cause the padlock key press to get lost (depending on the speed of your system you may or may not need this). You’ll notice that I have the padlock key alone programmed for the S3 chorded / I key press so that I can still walk my eye down the padlock target priority list when needed. If you don’t use TM gear, this may be a bit cryptic – just think of this as two buttons, one programmed to issue the sequence “2” (2D cockpit) then “4” (padlock) each time you press it once, and the other to issue “4” only each time. In any event and regardless of the view you are in now, any time I press T1 button, it drops me into Enhanced padlock with the highest priority threat in view.

Evaluating the Threat

So now you have the missile padlocked. How should you maneuver? Should you maneuver at all? In most cases the answer will be yes, you need to maneuver to evade. But sometimes, that isn’t the case and there’s an easy way to tell if you are already safe.

The rule of thumb is that if the missile is obviously moving at a steady rate across your canopy then it probably isn’t tracking you at all. In other words, if the padlock view is moving as though your head is swiveling to follow the missile, it’s not tracking you. Relax and enjoy the view. By the way, it’s much harder to judge whether the missile’s relative bearing from you is changing (i.e. moving across your canopy) if you are also turning. I usually try and stop any turn I have going and then watch the missile for a second or two to assess its course.

There’s another more foolproof way to know whether a missile is tracking you or not: the “7” key will take you to an outside view of any missile that is guiding on you. No view of a missile when you hit “7?” No immediate threat! You may consider use of outside views a “cheat” but regardless of that, I do not recommend this view since I find using this radical a view switch too disorienting in the heat of battle.

The rule of thumb arises from the fact that the missiles in Falcon 4 fly lead pursuit courses. As you will recall from Intercept Geometry 101, the shortest path to an intercept is a collision course, which is most easily arranged by keeping your target at a constant bearing from you as you close with it. This is exactly what the missile is doing to you as it tracks, so if it’s standing still on the canopy as you watch it, it has a collision course plugged in. What this tells you is that you need to activate your defensive plan. This means powering up ECM to counter radar guided threats if you haven’t already done so, dispensing countermeasures and maneuvering to defeat the missile’s collision course plans.

While there are lots of threat systems modeled in Falcon 4, for the purposes of this discussion we will consider just two: the SA-6 and the SA-8. Both are radar guided. Thus, ECM on and your finger on the chaff dispenser are the first order of the day in both cases.

Beating the SA-6

The SA-6 is an older system. In the Falcon 4 universe, it seems to be vulnerable to countermeasures, especially if you can catch sight of the missile shortly after lift-off. Pumping out three chaff bundles in quick succession is often enough to confuse it right off the bat. When this happens, missiles tend to either go ballistic (meaning straight up) or drive behind and below you, presumably chasing the chaff. In either of these cases, it’s quite obvious that the missile is moving rapidly across the canopy as you look at it. Don’t waste any energy maneuvering since it’s not necessary and you may need to preserve energy for the likely second volley.

If, on the other hand, the missile turns hard towards you and then appears to be standing still, moving very slowly on the canopy, or worse yet, apparently slowing to a standstill, more drastic measures are required. This is where a combination of beaming and chaff come into play. Put the missile on the beam and show it two or three chaff bundles. Then reevaluate the missile’s course.

If this all sounds to you pretty matter-of-fact, it should. Perhaps the worst thing you can do is panic and pull manically on the pole at the first sign of a launch in the hope that some maneuver, any maneuver, will save your bacon. “Lose sight, lose the fight” applies just as well to missile evasion as it does to dogfighting. Stay calm and act deliberately. The more you practice missile evasion, the more you will discover that in fact you often have plenty of time to study the threat and make a judgment call on what to do before you react.

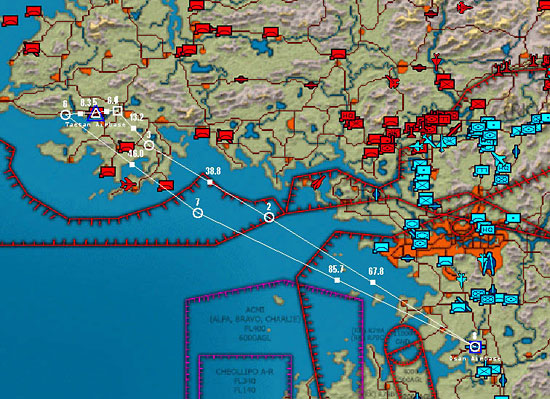

For BVR incoming missiles, putting the threat on the beam is best accomplished by using the threat warning TWS display to place the circled SAM site at the 3 o’clock or 9 o’clock of the display. If the threat is in your forward hemisphere, turn away from it to do this, and turn towards the threat if it is to your rear. You can monitor the TWS from the 2D cockpit view quite well to accomplish this.

If the missile is in visual range though, short missile flight times and lack of angular resolution in the display make using the TWS display much less effective for this purpose. Here padlock really comes into its own, especially if you are willing to use the lift line and SA bar cues (shift “3” key).

The lift line alone can help you put a missile at a beam aspect to you if you can point the line at the missile and maneuver until the missile is at the double chevron point along the lift line. You can then unload the G from your turn and roll the jet upright and you should find the missile at your three or nine o’clock (a.k.a. the 3-9 line).

For the ultra purists, it is of course possible to use only the canopy reflections to accomplish the same thing you can with the lift line. In that case you watch for your shoulders and visored face in place of the double chevron.

This works pretty well if the missile starts in your rear hemisphere and thus ends up “above” you when you roll and pull the double chevron towards it. You are less well off if the missile starts ahead of you since it would require a negative G push over, often of a magnitude beyond the capability of your virtual self and/or the jet, to keep the missile in view and center the lift line double chevron over the missile; not practical, but don’t despair just yet.

The SA bar adds another useful set of cues that can help even if you don’t want to bank (or often over bank for missiles well below you) to find a missile along the lift line. In the SA bar view, you can use the elongated canopy and the yellow view field rectangle to position a missile at the beam regardless of bank angle, attitude, and initial bearing to the threat.

To do this, simply maneuver to put the yellow cross in the view field rectangle in the middle of the elongated canopy. Again the double chevron on the lift line indicates the beam position, in this case supplemented by some green and red vertical tick marks. Turning to put the yellow cross anywhere along the line formed by the double chevron and the tick marks will locate the missile along your 3-9 line at a perfect beam aspect.

As with the BVR missile case, the direction of turn required to move the view field cross appropriately is determined by which hemisphere the missile is in. In the forward hemisphere, the missile will be below the tick mark / double chevron line and you should roll away from it and then pull to bring it to the line. In the rear hemisphere, you need to roll into the missile and pull to bring it to the beam.

The degree and attitude of the turn will depend on your situation. If the missile is closing quickly, you don’t have much time so turn hard and fast. If you are low on “smash,” consider turning nose low and selecting afterburner to generate best possible turn rate. If you are energy-rich, consider a climbing spiral since this puts you higher and thus further away from a SAM threat. Although in this case, beware the slowing effect the climb against gravity will have on your turn rate and your airspeed! Obviously if the threat is closer to your nose or tail, a more radical turn is also required to get it to the beam in time.

Also, you need to consider your loadout. With a full load of bombs, your ability to generate turn rate is much degraded, so consider whether you need to use the emergency jettison to lighten the load. It’s better to survive, abort the mission for lack of ordnance, and bring the airframe home than it is to end up in a smoking hole in the ground with bombs still on the racks. On the other hand, in a BVR situation you may be able to maneuver fast enough to beam a missile even with your wings laden.

As usual, you are likely to have more useful options available to you if you start out at or near corner speed, since most maneuver defenses rely on having your best turning capabilities available. Whatever you do, though, don’t get slower than 350kts with SAMs around, if you can help it.

As you approach getting an SA-6 missile to the beam position, pump out three more chaff bundles and slow your turn rate so you don’t overshoot the beam position, then assess the missile’s path relative to your view. Again, the SA bar can help you make this assessment, even if it’s not obvious from the main padlock view: look and see if the rectangle is moving even after you’ve eased the bat turn you used to get the missile at the 3-9 line. If the rectangle is moving quickly, you have probably beaten it already.

For SA-6s, most of the time, the above will keep you out of harm’s way. But sometimes one will get through anyway, at which point you probably need to think about a terminal phase defense. This situation is a lot more common with the SA-8, which seems far less susceptible to countermeasures and beaming techniques during the boost and fly-out phases.

Beating the SA-8

So if you face an SA-8 and both beaming and chaff have failed you, you are down to the last ditch terminal phase defense. As mentioned above, the principle here is taken straight from the textbook: a barrel roll about the missile’s approach access generates a rapidly changing set of target (that’s you!) headings for the missile to think about.

Since Falcon 4 missiles fly lead pursuit in all cases, a good radical change of direction on your part as the missile gets close will cause the missile to have to make its own even more radical change of direction. A continuous set of these turns by you makes the missile make ever more drastic corrections until finally the missile can no longer keep up the rate of change of turn required to keep the lead pursuit going and it falls off its collision course. At least, that’s the theory.

The best form of continuous turn you can make works out to be a barrel roll inscribing a circle about the axis of approach of the missile. The way to accomplish this roll is fairly straightforward, although the timing of when to start the maneuver is something you will have to try out and get the feel for yourself. First, get into position.

Assuming that you are already abeam to the missile in a somewhat level attitude and that the missile is approaching from below you, roll into the missile and pull to put your nose below the missile so that it ends up at your 10-11 o’clock or 1-2 o’clock position just above the canopy rail level. Obviously the required maneuver varies if you are in a different starting setup, but generally this picture is the result you want to end up with. You are ready to give the missile turn rate problems to solve and you are pointed down hill to keep your own energy losses to a minimum (missiles mostly come in volleys, so burning all your energy on the first missile unless you absolutely have to could be hazardous).

From this point, you need to initiate a barrel roll around the missile’s approach. A simultaneous roll (towards the missile) and pull from this starting point should accomplish this need. It may help you to think of this as “dragging” the visible parts of the cockpit (those that are on the display as you start) around the edge of your computer screen while padlock view keeps the missile in the center of the screen.

Often with the SA-8, less than one complete roll is enough to get the missile to fall off its collision course. I usually complete the whole roll, though, since it brings you roughly wings level again, making recovery easier to accomplish, even though it burns a little more energy than is strictly necessary.

Incidentally, SA-8s are also prone to the old trick learned in EF2000 by DiD. Since they pull considerable lead, under some circumstances you can easily run them into the ground! If you are only a few hundred feet AGL when you detect the launch and the missile is low to the ground still, a quick roll onto your back and a kick turn to point your nose at the ground can cause the missile to calculate a required intercept point well below ground level. The missile then obligingly dives for the ground and, provided it impacts terra firma before you do, and that you can then recover in time, the missile ends up a loser.

This works much better when the missile is in the forward hemisphere initially; I wouldn’t recommend trying it for a launch from behind you unless you are some way away from the SA-8 launcher already and have time to turn to put the missile in the forward hemisphere first. You may end up at low altitude with a launch in the rear hemisphere quite often against the SA-8s: imagine a first launch causes you to give up a lot of altitude in beating the missile with a diving barrel roll. You recover to wings level and start to angle away from the SAM launchers. This is just about the time those mischievous SAM guys love to lob a second missile your way.

Putting Theory into Practice

With advice on technique under your belt, all that remains is to practice until it comes naturally: train like you fight, fight like you train. You may already have a training game plan in mind, but if not, here’s the routine I use.

First, do like the pros do and run a simulation exercise. That may sound like a tautology flying a simulator game, but in this case we can do better than the air force and train against the actual threat with no danger of getting “morted” for real. Visit the setup screens and turn on invulnerability. While you are at it, turn on unlimited chaff and flares. This may seem sacrilegious, but it will take you a long time to get proficient at dodging SAMs if you practice in modes where your jet disintegrates after one or, at most, two SAM hits.

Figure 9 is a more robust smoke trail GIF.

Save this as <falcon directory>\terrdata\misctex\mistrail.gif

Another thing I’d recommend is using an enhanced version of the missile trail art file. The one I use was made by Jeff “Rhino” Babineau and does a great job making the smoke trails much more obvious, especially in the higher resolution modes. You may consider this a cheat, but I actually use this all the time since compared to what real-life video footage I’ve seen, the default Falcon 4 missile smoke trails seem rather puny (install it in your <falcon directory>\terrdata\misctex\ as “mistrail.gif”).

Once you’ve done this, take advantage of the Tactical Engagement Missile Threat training mission. This provides a canned setup with several different threat types all within a short flight time of each other. You can use the fact that you are invulnerable and that you have full tanks of JP8 and unlimited countermeasures to explore the fine art of missile evasion in this mission. Of course, a custom TE mission you make up to examine a particular threat setup will also work well. Either of these will save time-consuming efforts to hunt for trouble in mud moving instant action or actual campaign missions.

The first thing is to fly straight and level around the SAM sites. Forget maneuvering and watch the SAMs bore in on you. You may be surprised at how many miss even if you do nothing; as you fly past the sites, you are often beaming them as they launch and sometimes that’s enough. Be that as it may, you are trying to get a feel for what the missile paths looks like as they bore in on you for “successful” intercepts, as opposed to times when missiles pass you by. There is a boost phase where they seemingly start out ballistic. Then there’s a sharp turn to the lead pursuit course on the fly-out. Then they seem to slow down and stand still just getting a little larger each moment before rudely interrupting your concentration with a boom!

Fly the approach to the different SAM types at various altitudes to see the variation this causes in reaction. At low altitudes, the sites may have trouble picking you up at all. At high altitude, the SA-8 may choose to leave you alone entirely, even when you over fly them, since you’re on the edge of their envelope. And of course, try flying in the normally “no-fly” range between 500 feet and 10,000 feet. Even though for tactical reasons you shouldn’t plan to fly in this range on real mission flights, chances are SAMs or fighters will force you down into this range at some point leaving you in the heart of the medium-altitude SAM’s engagement envelope.

Try to watch the missile approaching to see if it is moving on the canopy or whether the yellow view field box in the SA bar is stationary or moving. If you catch yourself wondering whether the missile is moving relative to you or not because it looks almost stationary in mid air, that’s a sure sign that the missile is tracking you.

Also take note of missile flight times and get a feel for how much time you have between a launch warning and impact. Setting aside the “Archer inbou….BOOM!” scenario for a second, you may be surprised at quite how much time you really have, when dealing with SAMs, anyway.

You should also get your fingers used to stabbing the unpadlock-padlock button right when you get a launch warning to lock up the new threat. You may even want to develop a “nervous tick” and punch the button early and often when on the enemy side of the forward line of troops (FLOT). I consider this the equivalent of how real air force pilots are taught to scan the sky constantly. In any event, I usually expect to have newly launched radar missiles padlocked before my wingman calls them out and quite often IR missiles as well (yes, even the Archers sometimes).

Also, experiment with dispensing countermeasures. The first point is to make release of the right sort of decoys for the threat as instinctive as possible. In the heat of the moment, you want to make sure that you don’t end up pumping out flares in a vain attempt to confuse a radar seeker (hint: this doesn’t work!). Try and get a feel for timing of countermeasures releases and also think about quantity of chaff or flares to release. A rate of two to three per second seems to work quite well, at least as a place to start. In any case, recognize that sometimes less is more: too many chaff bundles in a row may just make a nice trail for the missiles to follow. If you intend to fly actual missions with the limited countermeasures setting turned on, you will want to find the balance between using enough decoys to be effective without spraying them all over the sky only to run out deep in bandit country.

Making a Game Plan

With this picture of how the SAMs work locked in your head, you can start to think about making the SAMs miss you routinely. Like many things in flying, a game plan in the form of a checklist may help you build good habit patterns in your training that will keep you safe when you fly in earnest.

- Honor the threat – Mainly rely on the audio launch cue and the cockpit missile launch light in the case of the radar SAMs, but otherwise seeing the plume of smoke from a fresh launch from padlock or virtual cockpit view. These are your cues that it is time to react right now!

- Locate the threat – If you haven’t spotted the threat by “Mark I” eyeball in Step One, find it now by locking it up in padlock view. You also want to determine range at this point, since appropriate action will vary if the missile is BVR, visual but at range, or right in your lap already. Either way, use padlock first on the assumption that the threat is close to ensure that you lose no time in the event it is in visual range already; you can always revert to BVR defense if the initial assumption here is wrong.

- Evaluate the threat – Is the missile guiding on you? If so, is it a heat seeker or radar guided? If you are using labels, you’ll know just from looking at the threat (you did your homework in Tactical Reference). If not and TWS indications don’t make it obvious, consider the threat heat and radar guided.

- Countermeasures and maneuver (as required) – Flares and reduced throttle as much as possible for IR heat seekers, chaff for radar missiles. Beam radar guided missiles at range. Barrel roll, break turn, or other nose rate maneuver to defeat missiles that are closer in.

- Reevaluate the threat – If the missile is still guiding, return to Step Four.

- Recover the jet – As soon as possible, you want to resume a normal flight attitude and start picking up any expended energy, be it airspeed or altitude. In Falcon 4, missiles tend to come in volleys, so you need to be back in the ideal configuration to start this list over again at Step One.

Conclusion

There is no perfect defense against SAMs in real life or in our simulated one. Even with perfect evasion technique, occasionally you will get tagged anyway. And I wouldn’t represent the techniques outlined above as anything other than the result of my own experimentation; there may well be better moves than these. Hopefully some of the lessons I learned from flying against the SA-6 and SA-8 systems as described above will give you some insight that is useful for your own flying. Perhaps you may even be inspired to try developing reliable methods to beat other systems in the Falcon 4 threat arsenal. If so, I wish you luck and don’t forget to spread the wealth when you come across that perfect move!