The tempo of the ground war through the first half of the 1960s was relatively slow. The primary enemy force was the ‘Viet Cong,’ a force of Vietnamese communist guerilla soldiers. The VC did not engage in large battles with US or ARVN (Army of the Republic of Vietnam), but, instead fought a ‘hide and seek’ type of guerilla warfare that was meant to break down the civilian populace’s trust and loyalty to the South Vietnamese government. As a result, the FACs in their O-1s were used piecemeal throughout the country in response to local firefights as they occurred. In addition to USAF FAC units, the VNAF (South Vietnamese air force) also flew the O-1. Both USAF and VNAF FAC units responded to mission tasking that originated in US military headquarters in Saigon.

Using VHF-FM radios, the FAC would contact the friendly ground force commander when he approached the target area. The FAC’s primary role was to act as the ‘eyes’ of the ground commander. He would attempt to visually locate the enemy ground force and would then advise the ground commander of their position. If the ground commander requested air support, the FAC would relay this request back up the communication chain. If fighter assets were available, they would be directed to fly to the target area and contact the FAC. Once in contact with the FAC, the fighters would be directed by the FAC on where to deliver their weapons.

The O-1 FAC had two methods of directing the fighter attack. First was his radio briefing in which he would describe the enemy location using prominent landmarks. Once the fighters acknowledged that they had the enemy location in sight, they would be cleared by the FAC to attack. A second method of directing the fighters was the use of marking rockets. These 2.75 inch rockets were carried in pods under the L-19’s wings and were aimed and fired with a rudimentary TLAR (That Looks About Right!) aiming reference. The rocket gave off a white smoke cloud and was easily seen from the fighter’s orbit over the target.

The primary US fighter in service in SEA during this time was the F-100 Super Sabre. The ‘Hun’, as it was popularly called, had evolved from a day fighter into a fighter-bomber. In its SEA service, it was typically armed with high drag 500 lb. bombs, napalm, and rockets. It also had 4 20mm cannon for strafe.

Fig 4 – F-100 Super Sabre

Other aircraft that operated in the CAS role in the early years included the B-57, A-26, and VNAF T-28s. The B-57 had been in the USAF inventory since 1955, serving as a light bomber in Tactical Air Command. The Canberra could carry a wide variety of weapons both internally and on wing pylons. In addition, it had 20mm cannon mounted in its wings. In Vietnam, the B-57 was used from 1964 to 1968.

Fig 5 – B-57 Canberra

The A-26 Invader was a twin engine World War 2 bomber that had seen considerable service also in Korea. By the time it was used in SEA, it was well past its prime, but in the relatively small scale war of the early 60s, the aircraft was adequate. By 1969, as the conflict expanded and the enemy AAA threat increased, the A-26 was withdrawn from service.

Fig 6 – A-26 Invader

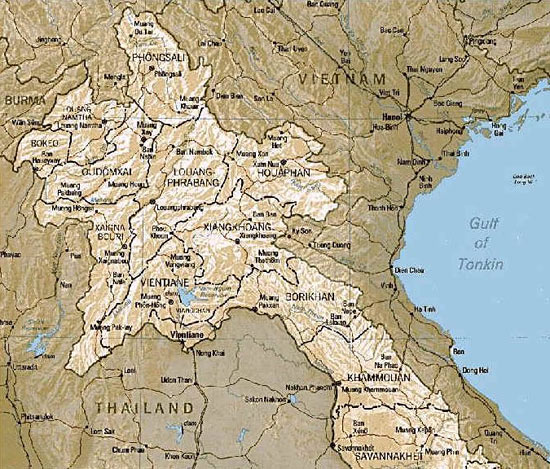

The VNAF flew the T-28 Trojan as a light attack fighter. The T-28 was a USAF trainer that was adapted to carry small bombs and rockets as well as machine guns. USAF pilots often flew as instructor ‘advisors’ with the VNAF in their T-28s. The Royal Laotian Air Force was also equipped with T-28s and US advisors and flew CAS sorties in Laos.

Fig 7 – T-28 Trojan

During this time, the standard mission profile was for the fighters to orbit over the target area while the FAC gave them a target brief. This briefing included the type of target, the target area elevation, known winds, position of friendly troops, attack restrictions, observed or suspected threats, and best bail out direction if needed.

As long as the fighters remained above about 5000’ above ground, they were safe from rifle and small caliber machine gun fire. The typical orbit altitudes in this low threat environment ranged from 5000’ to 10,000’. The fighters would form a rough circle overhead the target and would attack one at a time from the circle. This circle was known as the ‘wheel.’

Fig 8 – The Wheel

The FAC would clear each fighter to make its attack and would direct its aim point based upon how well the preceding fighter had delivered its ordnance. Often, the target would not be visible to the fighters. In this instance, the FAC would direct the fighters to aim relative to the previous fighter’s weapon impact…as in “Two, hit 100 meters west of lead’s bomb.” As long as the fighter’s weapons and fuel held out, the FAC could keep them over the target area to provide an umbrella of coverage for friendly troops.

By the middle to late 60s, however, the North Vietnamese had strengthened and reinforced the Viet Cong guerillas with regular North Vietnamese army troops. These forces were supported by an ever increasingly more lethal anti-aircraft capability. The USAF responded with the introduction of more capable and modern aircraft.